Z-machine

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2009) |

| Designer | Infocom |

|---|---|

| Bits | 16 |

| Introduced | 1979 |

| Version | 1.1 (2014) |

| Design | CISC |

| Endianness | Big |

| Open | Yes |

The Z-machine is a virtual machine that was developed by Joel Berez and Marc Blank in 1979 and used by Infocom for its text adventure games. Infocom compiled game code to files containing Z-machine instructions (called story files or Z-code files) and could therefore port its text adventures to a new platform simply by writing a Z-machine implementation for that platform. With the large number of incompatible home computer systems in use at the time, this was an important advantage over using native code or developing a compiler for each system.

History and design

[edit]Nomenclature and conventions

[edit]The "Z" of Z-machine stands for Zork, Infocom's first adventure game. Infocom used file extensions of .dat (Data) and .zip (ZIP = Z-machine Interpreter Program), but the latter clashed with the widespread use of .zip for PKZIP-compatible archive files starting in the 1990s, after Activision had closed Infocom.

Infocom produced six versions of the Z-machine. Files using versions 1 and 2 are very rare. Only two version 1 files are known to have been released by Infocom and only two of version 2. Version 3 covers the majority of Infocom's released games. Later versions had more capabilities, culminating in some graphic support in version 6.

The modern convention for Z-code files usually have names ending in .z1, .z2, .z3, .z4, .z5, .z6, .z7, or .z8, where the number is the version number of the Z-machine on which the file is intended to be run, as given by the first byte of the story file.[1] As previously noted, the Infocom games used the equivalent of .z1 through .z6; .z7 and .z8 were proposed and adopted after Infocom had shut down.

Before Z-machine

[edit]The MDL programming language was derived from Lisp at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology by the Dynamic Modeling group of the Laboratory for Computer Science (LCS) in the 1970s; inspired by Colossal Cave Adventure (1977), members of that group went on to write Zork in MDL, completing the initial version two weeks later.[2][3]: 5–6 Like Adventure, Zork was programmed for the DEC PDP-10; the finished version occupies 1 MB of MDL code and requires 512 KB of RAM to run. Because contemporary home computers did not have these resources, considerable effort was needed to port the game.[3]: 11 Eventually, the developers split Zork into two games for personal computers.[4]

The compression required to run Zork from floppy discs with approximately 80 KB of storage seemed like an insurmountable barrier to Blank. Berez realized that UCSD Pascal used a virtual machine (VM) model to generate executable files that could be readily ported across platforms, and together with Blank, they devised requirements for a lightweight VM optimized for text adventure games, which would retrieve data and execute instructions as needed from storage to compensate for the relatively small RAM sizes in typical microcomputers.[3]: 11 The resulting Z-machine used an object tree structure for in-game items, locations, characters, and weapons.[3]: 11 For comparison, the Z-machine parser occupies 3 kB of storage, while the original PDP-10 parser occupies 10 Kwords (36-bit).[5]

ZIL and ZIP, ZILCH and ZAP

[edit]To complement the Z-machine, Infocom developed the high-level computer language Zork Implementation Language (ZIL) by streamlining MDL,[5] and the Z-language Interpreter Program (ZIP), which complies ZIL into Z-machine instructions in a two-stage process; this made text adventure development platform-independent and enabled porting to different systems simply by writing an appropriate Z-machine interpreter.[3]: 12–13 ZIP consists of a compiler (ZILCH, short for ZIL Compiler Hack) and an assembler (ZAP, the Z-machine Assembler Program).[6]

ZILCH has never been released, although documentation of ZIL still exists, and an open-source replacement "ZILF"[7] has been written. After Mediagenic moved Infocom to California in 1989, Computer Gaming World stated that "ZIL ... is functionally dead", and reported rumors of a "completely new parser that may never be used".[8]

Graham Nelson and Inform

[edit]In May 1993, Graham Nelson released the first version of his Inform compiler, which also generates Z-machine story files as its output, even though the Inform source language is quite different from ZIL.

Inform has become popular in the interactive fiction community. A large proportion of interactive fiction is in the form of Z-machine story files. Demand for the ability to create larger game files led Nelson to specify versions 7 and 8 of the Z-machine, though version 7 is rarely used. Because of the way addresses are handled, a version 3 story file can be up to 128K in length, a version 5 story can be up to 256K in length, and a version 8 story can be up to 512k in length. Though these sizes may seem small by today's computing standards, for text-only adventures, these are large enough for elaborate games.

During the 1990s, Graham Nelson drew up a Z-Machine Standard based on detailed studies of the existing Infocom files. The standard also includes extensions used by his newer versions, as well as links to the "Blorb" resource format used by Infocom, and a "Quetzal" savefile format.[9] In 2006, Nelson expanded Z-machine to the 32-bit Glulx format for Inform 7. The Interactive Fiction Technology Foundation, founded 2016, manages all these standards.[10]

ZIL (Zork Implementation Language)

[edit]The ZIL is based on MDL from MIT. Here is the definition of Zork I's brass lantern in ZIL, with added comments to illustrate the meaning of each line:[11]

<OBJECT LANTERN #_Defines the LANTERN object

(LOC LIVING-ROOM) #_Defines the initial object location

(SYNONYM LAMP LANTERN LIGHT) #_Defines synonyms that can be used instead of LANTERN

(ADJECTIVE BRASS) #_Optional adjective to distinguish this lantern from other lanterns

(DESC "brass lantern") #_Short description in inventory list

(FLAGS TAKEBIT LIGHTBIT) #_What is this object capable of? It can be TAKEN. It provides LIGHT.

(ACTION LANTERN-F) #_Subroutine which defines special actions with this object

(FDESC "A battery-powered lantern is on the trophy case.") #_Description during first encounter

(LDESC "There is a brass lantern (battery-powered) here.") #_Later description in other locations

(SIZE 15)> #_Defines weight to limit inventory capacity

The equivalent object in MDL is defined as:

<OBJECT ["LAMP" "LANTE" "LIGHT"]

["BRASS"]

"lamp"

<+ ,OVISON ,TAKEBIT ,LIGHTBIT>

LANTERN

()

(ODESC0 "A battery-powered brass lantern is on the trophy case."

ODESC1 "There is a brass lantern (battery-powered) here."

OSIZE 15

OLINT [0 >])>

A more complex example involving combat, along with its MDL Zork equivalent, is presented in a 2019 blog post by Andrew Plotkin. Notably, the Z-machine has no support for garbage collection and ZIL has no concept of Lisp's list system.[12]

Interpreters

[edit]

Interpreters for Z-code files are available on a wide variety of platforms. The Inform website lists links to freely available interpreters for 15 desktop operating systems (including 8-bit microcomputers from the 1980s such as the Apple II, TRS-80, and ZX Spectrum, and grouping "Unix" and "Windows" as one each), 10 mobile operating systems (including Palm OS and the Game Boy), and four interpreter platforms (Emacs, Java, JavaScript, and Scratch). According to Nelson, it is "possibly the most portable virtual machine ever created".[13]

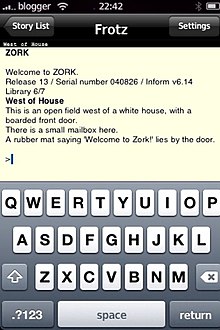

Popular interpreters include Nitfol and Frotz. Nitfol makes use of the Glk API, and supports versions 1 through 8 of the Z-machine, including the version 6 graphical Z-machine. Save files are stored in the standard Quetzal save format. Binary files are available for several different operating systems, including the classic Mac OS, Unix-like systems, DOS, and Windows.[14]

Frotz was written in C by Stefan Jokisch in 1995 for DOS. Over time it was ported to other platforms, such as Unix-like systems,[15] RISC OS,[16] and iOS.[17] Sound effects and graphics were supported to varying degrees. By 2002, development stalled and the program was picked up by David Griffith. The code base was split between virtual machine and user interface portions in such a way that the virtual machine became independent from any user interface. This allowed more variety in porting Frotz. One of the stranger ports is also one of the simplest: an instant messaging bot is wrapped around a version of Frotz with the minimum I/O functionality creating a bot with which one can play most Z-machine games using an instant messaging client.[18]

Another popular client for macOS and other Unix-like systems is Zoom.[19] It supports the same Quetzal save-format, but the packaging of the file-structure is different.

See also

[edit]- Glulx – Similar to the Z-machine, but relieves several legacy limitations

- Inform – A computer language that can produce Z-machine programs

- SCUMM – Script Creation Utility for Maniac Mansion by LucasArts, a graphical system similar to Z-machine

- TADS – Like Glulx, made to address some of its limitations

References

[edit]- ^ "The Z-Machine Standards Document". inform-fiction.org. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^ Lebling, P. David; Blank, Marc S.; Anderson, Timothy A. (April 1979). "Zork: A Computerized Fantasy Simulation Game". Computer. 12. IEEE Computer Society: 51–59. doi:10.1109/MC.1979.1658697.

- ^ a b c d e Briceno, Hector; Chao, Wesley; Glenn, Andrew; Hu, Stanley; Krishnamurthy, Ashwin; Tsuchida, Bruce (December 15, 2000). "Down From the Top of Its Game: The Story of Infocom, Inc" (PDF). MIT Course 6.933J/STS.420J (Structure of Engineering Revolutions). Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- ^ Lebling, P. David (December 1980). "Zork and the Future of Computerized Fantasy Simulations". BYTE. pp. 172–182.

- ^ a b Blank, Marc S.; Galley, S. W. (July 1980). "How to Fit a Large Program Into a Small Machine or How to fit the Great Underground Empire on your desk-top". Creative Computing. pp. 80–87. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ Plotkin, Andrew. "The Obsessively Complete INFOCOM Catalog". eblong.com. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- ^ McGrew, Jesse. "ZILF". zilf.io. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ "Inside the Industry: Infocom's West Coast Move Stirs Controversy". Computer Gaming World. No. 63. September 1989. p. 10.

- ^ "Inform - ZMachine - Standards". inform-fiction.org. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^ "Glk, Glulx, and Blorb Specifications". Interactive Fiction Technology Foundation. 16 November 2022.

- ^ Maher, Jimmy (January 7, 2012). "ZIL and the Z-Machine". The Digital Antiquarian. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- ^ Plotkin, Andrew (April 17, 2019). "What is ZIL anyway?". Zarf.

- ^ Nelson, Graham. "About Interpreters". Inform website. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- ^ "if-archive/infocom/interpreters/nitfol". Retrieved 2016-10-29.

- ^ "Frotz README file on Gitlab". Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- ^ "The RISC OS Frotz Home Page". 1999-09-18.

- ^ "Frotz on the App Store". App Store.

- ^ "Frotz DUMB file on Gitlab". Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- ^ "Logical Shift Zoom". Retrieved 2016-10-29.

External links

[edit]- The Z-Machine standards document

- Learning ZIL at the Wayback Machine (archived August 7, 2010) (PDF) is the Infocom ZIL manual from 1989

- Description of ZIP at the Wayback Machine (archived March 9, 2012) (PDF) the Z-Language Interpreter Program (Infocom Internal Document) from 1989

- Interpreters

- How to Fit a Large Program Into a Small Machine describes the creation and design of the Z-machine